Nov 2, 2022–Do only mammals play?

Nov 2, 2022–Do only mammals play?

This question caused some consternation around our Table of Knowledge. We all have seen films of otters, puppies, penguins, and ponies jumping, sliding, and kicking just for the joy of it.

But what about other classes in the animal kingdom? Someone pointed out a raven has been caught on camera sliding down a snowy roof. Movies have been made of octopi solving puzzles, and they are not only NOT mammals, they lack a spine altogether. You can’t tell me houseflies aren’t toying with us when they circle and land on your neck while you are trying to type up another Pulitzer-winning column.

But back to upright bipedal hominids.

I’ve always been an observer of how larval stage humans learn. Even as a teen, I was fascinated watching toddlers unravel the world around them. This interest led to a degree in Elementary Education, where we studied the importance of play.

In one of my first positions, I taught at an American School overseas where they neglected to tell me there was no curriculum for any of the subjects I taught, including science, social studies, PE, and music. So what did I do?

I went back to my own childhood and remembered how my siblings and I learned.

We played.

So for science, we built aquariums where we raised fish we caught.

For music, we wrote songs and put on plays we made up.

For social studies, we reserved a space at the local “feria” and sold American clothing to the natives.

For PE, we simply played games. All the playground staples like Red Rover, dodgeball, and wiffle ball. With the Kindergarteners, we played hide and seek. We didn’t have any inside gym spaces (it was 70 degrees year round and never rained), so this all happened outside on the playground, which was the Atacama desert. So it was quite a challenge to find places to hide.

This got me to wondering. In today’s world, where everyone holds all the world’s knowledge in their hand, where no one is allowed to ride their bikes to school or hang out on the playgrounds without supervision, or even gather on the corner under the streetlights, does anyone actually play anymore?

Do we still let kids do dangerous stuff?

I remember disappearing for an entire day, off to our timber, falling in the creek, walking at night in the snowdrifts, playing work-up baseball on the vacant lot by the railroad tracks. Using power tools as a 5th-grader, unsupervised (“Are you allowed to do that,” asked one babysitter. “Yes,” I replied, and I wasn’t lying.)

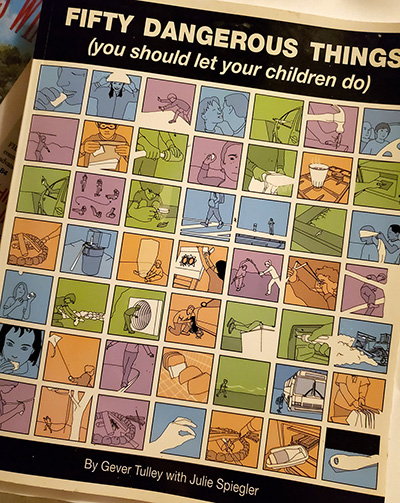

My son sent us a book call “Fifty Dangerous Things (you should let your children do),” by Gever Tulley. Just rereading it as my own grands are becoming my new guinea pigs for learning. The names of some of these activities will undoubtedly set you on edge:

- Lick a Battery

- Play in a Hailstorm

- Play with Dry Ice

- Put Strange Stuff in the Microwave (my 3-year-old grand discovered this sparkly adventure on his own)

- Throw Things from a Moving Car (my kids still remember sticking wooden matches in an orange and tossing it out the window to watch it light on fire)

- Burn Things With a Magnifying Glass (this was great sport at recess, but not for the ants)

- Squash Pennies on a Railroad Track (we did this during the previously mentioned baseball games when we were in the outfield and no one was hitting to us)

- Dam a Creek (every weekend)

- Whittle (Dad taught us this at a very young age–I have the scars to prove it, not listening to his advice, “carve AWAY from your body”)

- Play with Fire (what kid hasn’t?)

These sound dangerous to me now, as I have succumbed to the hysteria that the world is a dangerous place. Also because adults learn we are no longer bulletproof. However, Tulley, who runs a Tinkering School, has a compelling reason for advocating this type of play.

“I wrote this book,” he said, “because I believe that the best way to be safe is to learn how to judge danger.”

I wonder if that is something we have lost.