May 24, 2017–When is enough enough?

May 24, 2017–When is enough enough?

I’ve been trying to quantify the exponential futility of doing more.

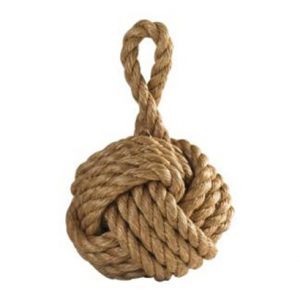

One easy way to visualize this is knot tying.

If the sole function of making a knot was to, say, fasten one object to another, we could achieve the goal in many ways. To hold a horse to the rail, for example, you could solve the problem with yards of rope and dozens of wraps around both the horse and the rail.

But that would be a waste of time, effort, and hemp.

The “art of the knot” is to accomplish the desired outcome with a minimum of material and effort. That is why some early outlaw invented the slipknot. With a short length of twine, a loop, a twist, a tuck and a pull–voila! A hitch that will hold the orneriest stallion, yet come undone with a tug of the end. The bay is secured and the scoundrel gets to his sarsaparilla sooner.

I first learned this technique of “minimal effort for maximum effect” in my drumming days. When packing up my set at the end of the night, I tightened stands just enough to grab and hold them. That made setup at the next club simple and quick. Didn’t even think about it until the time I allowed a husky fellow to help me pack up my gear. At the next gig, because my helper, in his sincere effort to help, had torqued down the wing nuts, I needed a pipe wrench to release them.

Wasted effort.

Once you are tuned to this phenomenon, you start seeing it in all parts of life.

While pushing the button on a drinking fountain, I realized I was leaning on it with enough force to bruise my thumb. I consciously relaxed my muscles until I reached the minimum input level to keep the water flowing. Not to overstate it, but the transformation on my body was all out of proportion to this simple act. It released tension in my back and neck, I breathed deeper, and the water was just as wet.

San Antonio Spurs center Tim Duncan, when he performed an eponymous dunk, was a genius at jumping just high enough to lift the ball over the rim. No windmilling, tongue hanging, rim clanging slash and burns from the top of the backboard. By the time Duncan’s dunks went through the bottom of the net, he was halfway down the court, playing defense.

It was no accident his career was so long and his game so efficient.

Writer Malcolm Gladwell even applied this concept to the highest level of decision making in his book Blink. My takeaway was that we often make better decisions when they’re not based on too much information. In fact, having more facts can lead to poorer or no decisions, the dreaded “paralysis of analysis.”

We have all experienced the flash of insight while making a major decision. It seems I agonize more over which brand of toothpaste to pick up than I ever did deciding to get a new car, purchase a house, or propose marriage.

There are endless examples when you start noticing. There is beauty in “less is more” in music, art, and basketball.

And writing. The best writers seem to know when to stop.